The Early Years of the College’s Independence: The Starr Era, 1962-2013

(Editor’s Note: Dr. Roy Knapp’s written history of the first 34 years of Antelope Valley College covered the college’s inception in September 1929 through the start of the presidency of Dr. James Starr in 1963.[i] There are some historical aspects absent from Knapp’s record that are foundational to the narrative, thus this historical account will begin in 1962 with the college’s first president, Dr. Lowell F. Barker.)

Antelope Valley College has been an integral part of Antelope Valley’s history, dating back to the college’s creation in 1929.

At the time, the area was largely rural and, due to transportation constraints of the day, was far removed from urban life of downtown Los Angeles some 70 miles away from the campus.

Community colleges have been a uniquely American institution first established in 1901 in Joliet, Illinois as an extension of a high school program.[ii] Antelope Valley College, originally called Antelope Valley Junior College, was like so many other such institutions of the day, deriving the “junior college” label by providing the first two years of liberal arts education for those pursuing a four-year college or university degree. For those without the resources or ability to attend four-year institutions far away, Antelope Valley College (AVC) provided an opportunity for graduates of the area’s only high school, Antelope Valley High School, to continue their education.

For the first decades of its existence, the college was an extension of Antelope Valley High School – utilizing space on the school’s campus on Division Street in Lancaster before establishing a temporary home across the street from the high school on 3rd Street East.[iii] As the college grew, officials expanded the scope of the curriculum to include vocational and technical courses.

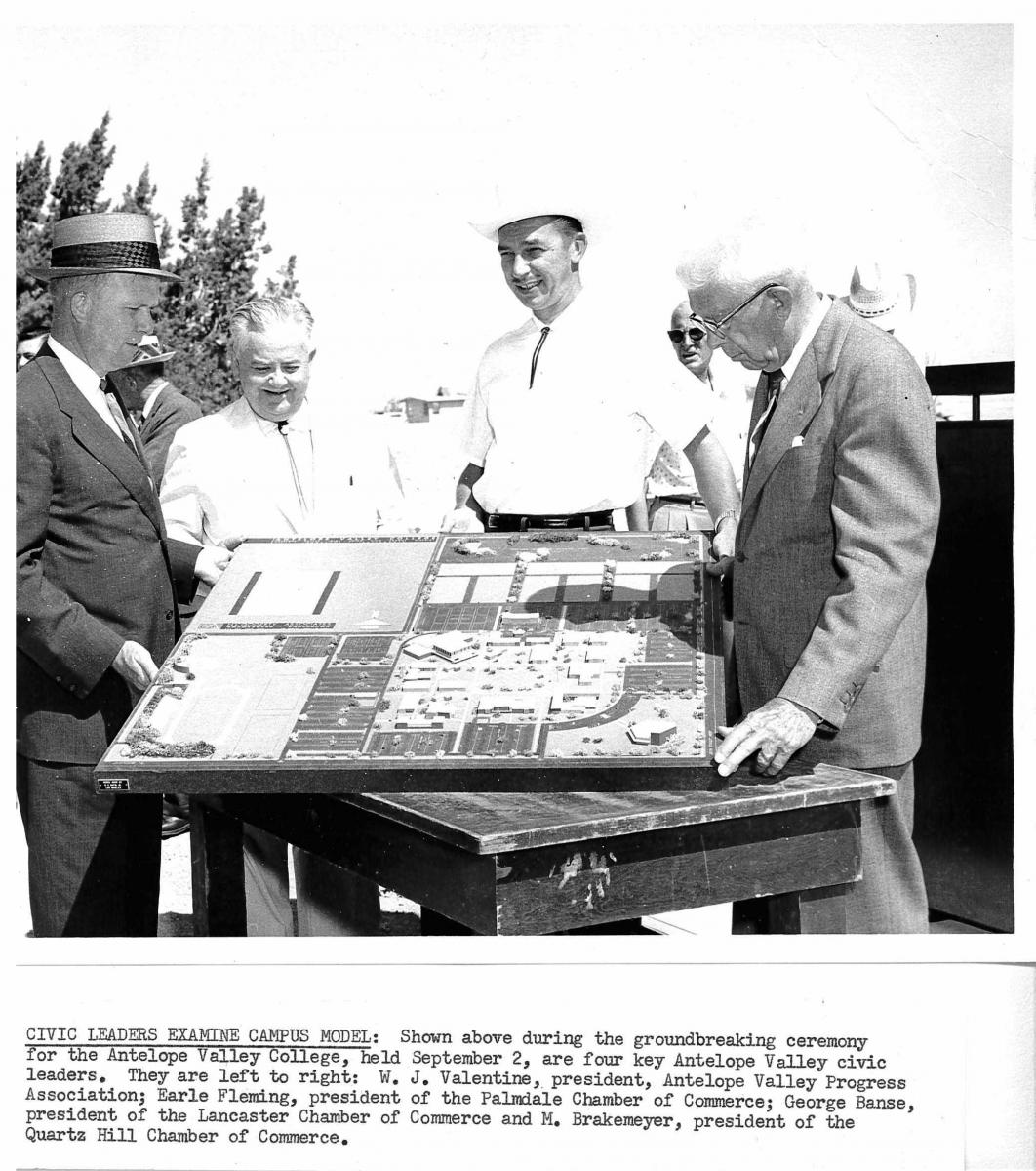

In 1961, the college opened a permanent campus on 110 acres at the northwest corner of 30th Street West and Avenue K in Lancaster.

“It was out in the sticks,” Frank Roberts said of the new campus. Roberts, a faculty member at the time, recalled in a 2015 interview: “The students didn’t want to come out there,” explaining that the center of town was a few miles to the northeast.

Graduation exercises were held in the new campus Gymnasium in spring 1961 – the first event held on the campus - even though the first classes weren’t held on campus until summer 1961. Aside from a Gymnasium, other campus buildings included an Administration building, Student Center, Library and several single-story lecture rooms/laboratories, as well as faculty offices. The campus was officially dedicated Nov. 14, 1961.

In December 1961, local voters approved the establishment of a separate junior college district. Then, in April 1962, another election was held to select a Board of Trustees for the new college district. There was keen interest in the election with 24 community members filing to run for the five board seats. Those winning the election were Ross W. Amspoker, Palmdale; Louis Massari, Lancaster; Charlotte Rupner, Lancaster; Glen A. Settle, Rosamond; and Chester A. Wolowicz, Lancaster.[iv]

The high school district continued to oversee the college until it formally separated from the high school on July 1, 1962. Prior to that, on May 7, 1962, the five newly-elected college board members were sworn into office by Los Angeles County Assistant Superintendent of Schools Dr. C.C. Carpenter.

"If education is what we believe it to be, it will determine the future of this country and protect the future of this country,” Carpenter told trustees.[v]

Carpenter went on to underscore the role of the trustees: “You have been selected by the community as board members. You have a tremendous responsibility. We would hope that as soon as possible you would develop board policies. The most important function is to develop a policy to determine the kind of educational system you will have. You should develop policy and then continually evaluate the policy. You should select the best chief administrator that you can because you have to depend upon him to represent you.”

The board unanimously chose Dr. Lowell F. Barker to be employed as Superintendent/President for the 1962-63 school year – continuing in a role as the college’s chief executive officer that he had accepted March 7, 1957 when the college was still under the governance of the high school district. Now, Barker had the added duty of superintendent for the newly independent community college district.

Other business conducted at that first meeting included:

- Selection of Ross Amspoker as board president, Chester Wolowicz, vice president, and Charlotte Rupner as clerk. The board officers would serve one-year.

- Trustees drew lots for their terms of office, with Glen Settle and Rupner drawing two-year terms through June 30, 1963 and the remaining three trustees with terms through June 30, 1965.

- Affirmed the name of the new entity as Antelope Valley Joint Junior College District.

- A presentation on a tentative 1962-63 budget, which included discussion of California’s new law requiring that 50 percent of the college’s expenses must go to classroom teachers. Barker told trustees the tentative spending plan only allotted 45 percent for teacher salaries.

- Rehired for 1962-63 tenure-track faculty members for the college – individuals already employed at the college through the high school district. They included Jose Avike, Gladys Baird, Marguerite Barsot, Louise Bercaw, Glenn Buten, Alice Buntin, Madeline Chapman, Roy Clifgard, Irwin “Bruce” Cohen, Donald Ekstrum, Emil Fernandez, Truman Fisher, Evelyn Foley, Jack Frost, Robert W. Fuller, Paul Greenlee, Karl Hardin, Rachel Harrison, Jack Held, Warren Houghton, Austin Jordan, Bernard Kelly, Lorna Knokey, Marguerite Knowles, Robert Lundak, Dean of Instruction Clyde C. McCully, Ruby McNinch, William Montamble, Gail Newkirk, Eugene “Russ” Niles, Warren Nunn, Lila F. Ogden, Charles Parker, Robert Parker, Alban Reid, Frank Roberts, Francis Rogan, Dean Russell, Marion Saunders, Harry P. Schmidt, Dean of Student Personnel Eugene Schumacher, Richard Thompson, Henry Wells, Selmer Westby and Delbert “Bucky” Wolter. (At a meeting two weeks later, trustees added E. Revier Palmer to the list of faculty.)[vi]

Trustees also got a look at the college’s schedule of classes – the first classes of the new college district -- to be offered during the summer session beginning July 2, 1962. The courses included “Painting and Drawing Techniques,” “Principles of Accounting,” “Electronic Circuit Analysis,” “Basic Engineering Drawing,” “English,” “American History,” “Plane Trigonometry,” “Speech,” and “Advanced Vocational Nursing.”

Dr. Lowell Barker was not even a year into life on the new college campus when in February 1963 he requested a release from his contract effective Feb. 23 to enable him to accept a four-year contract as the superintendent-president of Merced College, a new community college in Central California. “The opportunity to help a new community develop a junior college is a challenge and a golden opportunity to make a worthwhile contribution,” Barker wrote in his letter of resignation.[vii]

Trustees approved Barker’s release and appointed chief instructional officer Clyde McCully as acting superintendent-president while the board sought a permanent replacement.

One of the first additions to the campus came in spring 1963 with the installation and dedication of the Douglas Aircraft Company Skyrocket, D-558-2. The Skyrocket, one of only three Skyrockets in existence, was a sister to the Skyrocket that made history as the first aircraft to fly twice faster than the speed of sound. The aircraft carried the insignia of NACA, the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics -- the predecessor of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The plane had been at the old campus temporarily and was formally dedicated at its permanent home on the AVC campus on May 10, 1963.

One of the initiators for the Skyrocket coming to the college was Alden B. Carder, a member of the high school district’s board of trustees and manager of flight test for Douglas Aircraft. The Skyrocket was one of the planes Carder tested, according to his son, Brent Carder, who would later go on to work for the college as its head football coach and dean of physical education and athletics.

Meanwhile, Assistant Superintendent of the Los Angeles County Schools Dr. C.C. Carpenter was asked to lead a search committee for the new president. Following interviews with board members, Dr. James M. Starr was chosen from among 44 candidates to lead the college.

Starr was president of the Wenatchee Valley College in Wenatchee, Washington. He had a bachelor’s degree in business and economics from the University of Washington as well as a master’s and doctorate. Starr began his new position July 1, 1963 at an annual salary of $16,500. He was officially inaugurated on Nov. 8, 1963.

Starr was president of the Wenatchee Valley College in Wenatchee, Washington. He had a bachelor’s degree in business and economics from the University of Washington as well as a master’s and doctorate. Starr began his new position July 1, 1963 at an annual salary of $16,500. He was officially inaugurated on Nov. 8, 1963.

At Starr’s first meeting as president on July 1, 1963, business manager William T. Pickford told trustees that the district would be a bit smaller effective July 1, 1964, as the rural Kern County elementary school districts at Randsburg and Johannesburg would become part of the Kern County Junior College District through annexation.

Starr set about the task of guiding the new campus of the growing college.

One of Starr’s first actions was to recommended that trustees formalize the official name of the college as Antelope Valley College, instead of Antelope Valley Junior College. Starr reasoned that people had long referred to the institution as Antelope Valley College. Trustees agreed and changed the name.[viii]

The new title reflected the college’s greater role as more than just a liberal arts college, but rather a comprehensive community college. The college broadened its original education mission with establishment of vocational education programs in such areas as licensed vocational nursing and electronics – a response to community needs.

In fall 1963, officials were approached by one of the local aerospace companies, North American Aviation, which was in desperate need of more skilled welders. The college, which had a waiting list of 75 people wanting to enroll in the college’s basic course in welding, agreed to add two more welding sections financed by North American Aviation. The action was the first of many whereby the college would respond quickly to the needs of area business and industry to create new or revise existing vocational courses to train local residents for jobs.[ix]

Within a few months of his arrival in the new community, Starr created some concern with the faculty and at least one trustee in fall 1963 with a proposal to create a “staff activity record form,” which would be used to track the involvement of instructors in activity outside the classroom.

The new president’s intent was to gather information on the activities of instructors, information that might be used in determining salary awards for exceptional service, Dean of Instruction Clyde McCully told trustees during a meeting.[x]

“I would be concerned that we may be creating an image of a faculty member who is a service club member,” board President Ross Amspoker said. “This would not necessarily make of me a good lawyer. I would rather a person do an excellent job in the classroom.”

Despite Amspoker’s concern, trustees consented to Starr’s request to distribute a survey on staff activity.

“A new president would come in and everything would change in the college,” recalled long-time faculty member and administrator Frank Roberts, who served under five college presidents during his tenure.[xi]

The matter of merit pay for faculty members would be an ongoing topic at board meetings.

Among other matters trustees had to deal with in the infancy of the district were requests for college district residents to attend other community colleges and quality and design concerns of the college’s new buildings.

After opening of the campus in 1961, deficiencies in the construction of the campus buildings were a frequent topic of discussion at board meetings. Problem areas included decorative tiles on the exterior of the Administration Building, Student Center and Gymnasium, a defective beam in a shop building, the Gymnasium roof and problems with the Administration Building’s air handling system.

Trustee Chester Wolowicz reported to his fellow board members in February 1964 regarding a meeting he had with campus architect H.L. Gogerty and his subsequent recommendation that the architect be released from a contract with the district. Wolowicz reported that the architect recommended payment to contractors in instances where work hadn’t been completed.

“Mr. Gogerty said that he was depending upon his field people to check on the job. I feel that there is a very loose operation going on. Another factor was that the county inspector came out and said that the job was all right. It struck me that there has been complete deficiency in the overall operation in the past. The board should contact a few other architects, talk to them, and give the whole matter complete consideration.”[xii]

Trustees made attempts to have corrective actions by contractors and the architect, including involving county legal counsel in the drafting of letters to contractors seeking remedies to the problems. Eventually, some of the issues were resolved by contractors, the architect and other corrective work paid for by the district.[xiii]

With the opening of a new campus, the college began to host community service programs that included prominent guest speakers and concerts.

As evidence of the college’s growing role in the cultural life of the community, trustee Charlotte Rupner advocated keeping Community Concerts at the college rather than moving them to Antelope Valley High School. Rupner spoke of AVC’s new role in the community saying “the college should be the center of cultural activities.” In addition, she advocated for the purchase of a Steinway piano to be used in conjunction with Community Concerts.[xiv] Subsequently, the board approved the use of community service funds for the purchase of a seven-foot Steinway for $3,755 from a bidder, Los Angeles-based Penny-Owsley Music Company.[xv]

By the college’s third year at its new site, officials began discussing plans for further expansion of the campus, as well as shifts in priorities.

Starr called to the attention of board members what he described as an imbalance in the college curriculum with more emphasis on science, math and engineering. He called for a greater focus on the liberal arts, social sciences and vocational.[xvi]

“He absolutely believed that all you needed was a good liberal arts education,” recalled Frank Roberts of Starr’s stance against career/vocational education.[xvii]

Years earlier, the Soviet Union’s Oct. 4, 1957 launch of Sputnik I, the world’s first satellite, marked the start of the space age and the United States-Soviet Union space race. Concerns that the Soviet Union was more technologically advanced than America prompted a renewed push in math, science and engineering across the United States.[xviii] Locally, Antelope Valley College officials started an engineering curriculum.

Starr recommended that the district start work on a bond election or a tax override to fund completion of the campus master plan.

“I sense that the board feels: 1) that the public is interested in expanding their college when the time is right; 2) that it is not necessary to complete the entire campus at once; 3) that the tax burden should be spread over a period of time in accord with the needs of the college, and 4) that the board wants us to pursue available sources of income and keep them advised as to deadline dates.”[xix]

With the college continuing to operate under a low tax rate of 35 cents per $1,000 assessed valuation, money was a continual challenge, both for the ongoing daily operations of the college and for construction to accommodate the growing student enrollment.

By spring 1965, the board was ready to consider placing before local voters a request to sell construction bonds to help the college complete its master plan to accommodate 2,500 students.

Starr reported to trustees: “Operations-wise our assessed wealth is coming up in the neighborhood of 3 percent per year and our student body is increasing approximately 12 percent per year. The assessed wealth per student continues to go down.”[xx]

Schumacher affirmed Starr’s observation, claiming the local district was “about 24 percent below the average” statewide in assessed wealth per average daily attendance (ADA).

Starr went on to report that some faculty members had questioned the wisdom in constructing more labs and classrooms when the district couldn’t pay reasonable salaries. Some advocated restricting enrollment in order to maintain a sound academic program for a limited number of students.

“From my point of view my students are not getting the full-quality program that they deserve because of lack of facilities for speech and music in which Mr. (Glen) Horspool will bear me out,” faculty member Jack Held told trustees. “If we don’t have the facilities now, regardless of whether we increase the number of instructors, it is impossible to do a good job of teaching. We are going along in such a Mickey Mouse way that it is an insult to students and to the instructor. I know my hair is getting grey and thin. I don’t know whether a few more hundred dollars would increase my longevity or make is possible to do a better job. All I’m asking for (are) the tools to do the job.”

On a 4-1 vote with trustee Chester Wolowicz dissenting, the trustees approved a $1.9 million bond measure to appear on the ballot of a special bond election set for Oct. 19, 1965. The non-traditional election date was recommended by the Los Angeles County Superintendent of Schools on the belief that people hadn’t received their tax bills for the year and voters “are usually favorable to the schools at this point.”[xxi]

Far beyond the quiet confines of the AVC campus, the first hints of social upheaval that would so characterize the 1960s got the attention of local officials.

Civil rights advocates, including many university students, had protested against racial discrimination by employers in the San Francisco Bay area in 1963 and 1964. That was followed in fall 1964, by students at the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) protesting a ban on campus political activities. That launched the Free Speech Movement. News and images of the student activism and involvement on the UCB campus went worldwide.[xxii]

One incident included the arrest of a man who had set up a political information table on the Berkeley campus. Following his arrest, an estimated 3,000 students surrounded the police car containing the protester, deflated the tires of the police car, and prevented the car and the protestor from moving for more than 30 hours. Another protest of students occupying the UCB administration building resulted in the arrests of more than 700 students.[xxiii]

The Northern California unrest prompted AVC President Dr. James Starr to ask trustees how they wanted to deal with issues of free speech on the local campus. Also, it marked a clear departure from how the college had dealt with such student issues while still a part of the high school district.

“How far does the Board feel we want this institution to go in giving the students the right to determine their own political and social destiny on this campus?,” Starr asked trustees in May 1965.[xxiv] “Does the Board want to keep the control within the administration and faculty? To what degree do we want free speech on this campus? Do we want to bring on this campus certain questionable political parties?”

Trustee Wolowicz expressed general support for AVC students wanting to express themselves, yet he stressed that they should not be permitted to go through any kind of actions as occurred at Berkeley.

“I have a good deal of confidence in our American students,” said fellow trustee Amspoker, “and they should be allowed freedoms commensurate with those we demand for ourselves. I believe that they will act responsibly in a given situation. We should not be afraid of inviting controversial speakers to our campus as long as we make arrangements that all viewpoints on … certain issues are being presented.”

Not all trustees were in agreement.

“I feel it is up to the administration and, knowing the community, it would not be to the best interest of the college if we had a questionable person appear on the campus – a person that would stir up a certain amount of fervor that is not to the best interest of our institution,” said trustee Rupner. “We can’t afford to have a controversial figure on our campus. I feel that the administration is aware of this, and it should be within its power to see that such a person does not appear.”

President Starr told trustees that he would devise a policy that would embrace the concept that “learning should be such that the student should have an opportunity to make a decision.”

The policy would be exercised in future years.

During spring 1965 board elections, original trustee Chester Wolowicz failed in his re-election bid to Dr. Harry L. Deutsch.

Wolowicz summed up his time on the board with a prepared statement he made in his final board meeting on June 21, 1965. In it, he noted his desire to see a merit pay system for faculty members, instead of the traditional salary schedule based on years of experience and academic credit.

“I would like to say that the three years I have been on the board have been extremely challenging – not frustrating,” Wolowicz said. “I believe that in the last three years I have made a number of worthwhile contributions and owe nobody an apology, for the battles and arguments I have been involved in are part of the game.

“When it comes to the matter of faculty salaries, and having seen the professional performance of some of the faculty, my convictions are even more confirmed that a merit plan is best and would like to see a merit operation for those teachers that are outstanding.”

Wolowicz went on to claim that a minority of faculty members not wanting merit pay were “holding the reins” and had defeated him in the election.

“Whatever action you take under the present situation, you will always have dissatisfaction,” Wolowicz continued. “I can honestly say the morale of the faculty is not high. It is low. Until a whole new approach is taken, it will continue to be low. Salary increases alone are not the answer.”

He referred to the district’s desire of trying to keep faculty salaries at the statewide median.

“Thinking in terms of the median produces a median faculty. Much work must be done,” Wolowicz said.

Wolowicz closed by expressing his belief that a “lack of definitiveness” by the board and reversal of decisions had created confusion for the administration and faculty.[xxv]

At the same meeting, fellow trustee Glen Settle submitted his resignation as a board member, effective July 1, 1965

With Settle’s resignation right after the election, trustees filled the vacancy by appointing Robert E. Nelson, a 54-year-old Stanford University graduate who had served previously on the board of the Southern Kern County School District.

With the lone board member opposed to the bond election now out of office and the board back to five members, trustees set about the task of advancing the bond measure. Trustees hoped to use the revenue from the local bonds to combine with more than $250,000 in state matching money to construct a 2,000-seat concrete stadium to include a playing field and quarter-mile track, an English and Social Sciences Building, faculty offices, a fine and performing arts complex with four buildings including a “Little Theater,” Music Building, Art and Homemaking Building, and faculty office and Journalism Building.

To underscore the need for more campus facilities, officials had witnessed an increase in the student population since the new campus opened. However, aside from whatever population growth was occurring in the Antelope Valley, there was another significant factor at work: drafting of young men to fight in the Vietnam War.

Dean of Student Personnel Eugene Schumacher told trustees at a Sept. 7, 1965 board meeting that fall semester opening day enrollment was 1,383 day students, of which 1,116 were full time. With enrollment continuing through early September, he expected another 100 students to enroll for an increase of “at least 14 percent in day enrollment and a much higher increase in full-time … enrollment.”

Schumacher noted that students who would normally register as part-time students had registered as full-time students in order to avoid selective service obligations and being drafted into military service, since full-time students could avoid being drafted.

Whatever the reasons were for the growth, voters proved supportive on the Oct. 19 special election. Of 4,133 votes cast in northern Los Angeles and eastern Kern counties, 2,895, or 70 percent of voters, approved the sale of $1.9 million of construction bonds for the college district. Two-thirds of voter approval was needed to win the election.

In spite of the promise of new buildings, officials continued to debate over tax funding levels and budget.

After a year on the board, appointee Robert Nelson in June 1966 emerged with a plan to reallocate money from the district’s nearly half-million-dollar reserve fund. Nelson remarked that such a large cash reserve was embarrassing and that the money should be used to construct outdoor athletic facilities, freeing up bond money and state funds to be used for the campus building program.[xxvi]

Nelson’s proposal drew a sharp response from Superintendent Starr who told trustees “he would fight this to the death.” Starr advocated for enriching and expanding the college’s instructional program, including introducing televised instruction, computer instruction and adding agriculture facilities.

“We have reached the place where we need to enrich our instructional program,” Starr said. “We have a track at the high school that can be used until we can get to it.”

Starr said he knew of only three California community colleges with less than a 35-cent tax rate. Starr said that rather than cut the college’s tax rate, as suggested in a comment by trustee Amspoker, AVC should enrich the instructional program in vocational and adult education classes.

Advocates for an agriculture program wasted little time in developing plans by inviting agriculture educators from four-year colleges to come to the area for discussions in September 1966.

As development continued at the Lancaster campus, some questioned the idea of developing a second college campus in the Antelope Valley.

Don Hanson, a reporter for the Ledger Gazette newspaper asked officials at an Oct. 17, 1966 board meeting if any consideration had been given to the purchase of land for a second college site.[xxvii]

Superintendent Starr replied that it would be several years before a second college would be needed since the present enrollment was 1,700, almost half of what Starr felt could be accommodated.

Trustee Deutsch and several board members expressed a desire to look for land for a second college site, due to the increasing costs of land.

“When present campus enrollment reaches 3,000, consideration will be given to another campus, probably in the south valley area,” Superintendent Starr told trustees during another meeting three weeks later. “The Palmdale area has been looked over for possible sites but this is as far as the investigation has gone.”

The discussion ended with a board member recommendation that the administration contact county and state officials to review future population trends to better understand the need for a second campus in the Palmdale area.

Further expansion of AVC would need to be undertaken by another chief executive, however. On Dec. 5, 1966, trustees released Starr, with deep regret, from his contract with Antelope Valley Community College District so he could take a new job as superintendent of Yuba College in Marysville, effective June 30, 1967.[xxviii]

In his remaining months at AVC, Starr oversaw a recommendation to launch an agriculture program (to begin in fall 1967) and directed bond proceeds toward completion of buildings in the campus master plan.

Buildings recently completed or under construction were a Social Science Building, English Language Building and Faculty Office Building.

Planned construction projects included the stadium, with track, field and grandstand, and the four buildings to surround the Fine Arts Quad: the Home Economics, Music, Drama-Speech, and Communications (photography, journalism) buildings.

Also leaving the college was Dean of Instruction Clyde McCully, effective June 20, 1967.

On June 19, 1967, trustee Rupner announced that the board had selected a new superintendent-president, William N. Kepley Jr., from the Los Angeles city schools system. Kepley was to begin a four-year contract on July 1, 1967 at an annual salary of $25,000, plus health benefits.[xxix]

Starr had overseen the early growth and development of the new college campus, positioning it as an integral part of the community.

#

Works Cited

[i] Knapp, Roy A., “A History of the First 34 Years of Antelope Valley College: 1929-1963,” 1966,

[ii] “Community Colleges Past to Present,” American Association of Community Colleges, 2016, website: http://www.aacc.nche.edu/AboutCC/history/Pages/pasttopresent.aspx

[iii] Knapp, Roy A.

[iv] Knapp, Roy A.

[v] “Minutes, May 7, 1962,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[vi] “Minutes, May 7, 1962,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[vii] “Minutes, Special Meeting, February 11, 1963,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[viii] “Minutes, October 7, 1963,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[ix] “Minutes, October 7, 1963,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[x] “Minutes, Dec. 2, 1963,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xi] Roberts, Frank, Interview by Steven G. Standerfer, June 4, 2015

[xii] “Minutes, February 3, 1964,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xiii] “Minutes, October 5, 1964,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xiv] “Minutes, Sept. 8, 1964,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xv] “Minutes, October 5, 1964,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xvi] “Minutes, October 19, 1964,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xvii] Roberts, Frank

[xviii] “Sputnik and the Dawn of the Space Age,” NASA, 2016, website: http://history.nasa.gov/sputnik/

[xix] “Minutes, October 19, 1964,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xx] “Minutes, May 17, 1965,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xxi] “Minutes, October 19, 1964,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xxii] Freeman, Jo, “The Berkeley Free Speech Movement,” 2016, website: http://www.jofreeman.com/sixtiesprotest/berkeley.htm

[xxiii] “The Free Speech Movement,” 2016, website: http://www.calisphere.universityofcalifornia.edu/themed_collections/subtopic6b.html

[xxiv] “Minutes, May 3, 1965,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xxv] “Minutes, June 21, 1965,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xxvi] “Minutes, June 20, 1966,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xxvii] “Minutes, October 17, 1966,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xxviii] “Minutes, December 5, 1966,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board

[xxix] “Minutes, June 19, 1967,” Antelope Valley Community College District Governing Board